My curiosity inspired a few years of casual research regarding the provenance of the many rivers that divide Central Texas, those catalysts of swimming holes, welcome respite from the summer heat.

Guadalupe, Colorado, Comal, Frio—they spread like fingers through my summer stomping grounds in Austin, cutting paths for themselves through the granite of the Hill Country before meandering into the flat plains east to the Gulf of Mexico.

Rivers, I was aware, came from high places; I always imagined them coming from mountains, springing from the sides of rocky crags and drinking up melting snow. In the case of the myriad rivers of Central Texas, that high place is the Llano Estacado. The rivers of my Texas summers traced like rattlesnakes up, up, up into the arid flatness of the Llano, beginning—or ending, to my particular way of seeing—in dusty creek beds. The lucky ones might see the mountains on the horizon, but most were alone but for the mesquite and roadrunners.

I drove west from Dallas in a rented Audi, driving faster than I normally would. It felt correct, smooth. The in-dash GPS system ticked my altitude ever upward—a slow, almost unnoticeable climb across northwest Texas. The sunset was fervid and almost unbelievably long. In a place that flat, you see the entire sunset, from the moment the sphere slides out of view to the last glimmer of twilight, the circle of horizon a wash of cobalt and purple. I wondered, if I drove fast enough, if I’d keep seeing the sun setting all the way to the mountains.

I pushed late into the night, far later than I would have with anyone but the most steadfast of companions.

I drive farther alone.

I crossed the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River, which is probably too adorable a name for any river, and the road began noticeably, slowly but quite steadily, to climb. I noticed the eighteen-wheelers were tucked into the right lane, straining up the steady incline. I flew by with the cruise control on. I watched the altimeter tick upward. I realized if it weren’t pitch dark, I’d see it—the Caprock Escarpment of the Llano Estacado, the “Staked Plains.” It felt like a boundary, an imaginary dividing line. I was different once I crossed it, rolling into Amarillo, the bright city lights too bright after so long driving in the darkness.

In this moment I found myself, suddenly and perceptibly, somewhere else.

Around midnight, I stopped at a rest stop to use the restroom and stretch my legs. I wandered, stretching, in small, loose circles in the parking lot, verging on the low shrubs and grass just off the pavement, within looming view of a large sign reading “WATCH FOR RATTLESNAKES.” I stood for a moment and contemplated the pair of flashlights in the trunk of the car, considered taking a walk off the path a ways, but ultimately decided it was a bed—and not a nighttime encounter with a rattlesnake—that most interested me.

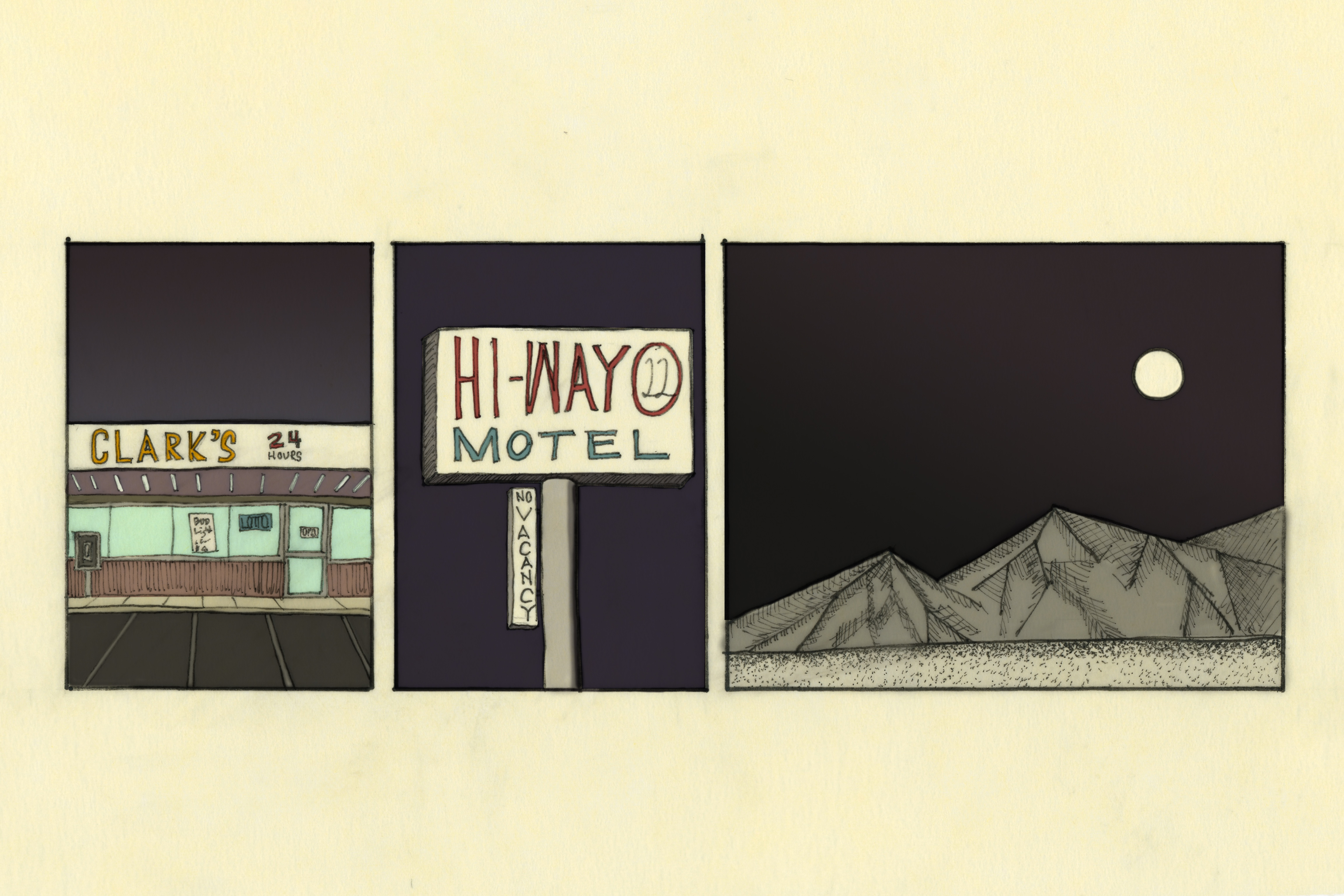

Tucumcari serves as the first sign of life along the interstate in New Mexico headed west, and boasts itself the largest point of civilization between Amarillo to the east and Albuquerque to the west, a 300-mile shot through West Texas plains into idyllic Southwestern high desert. Tucumcari is a sort of living museum to the fading history of Route 66; vintage motels with restored neon signs and antique cars facing the main east-west thoroughfare, the Mother Road herself, are now mostly deserted but for a trickle of locals and history buffs. At the west end of town, she rejoins the interstate among the skeletons of old gas stations and roadside diners.

Of course, I knew none of this when I crossed once again from the darkness into the lights of civilization, exit 335, and ducked into the Motel 6 which sat conveniently at the end of the offramp. I paid through the drawer of a glass window, the attendant making no eye contact, got my room key and disappeared into the musty darkness of the cheap motel room. I woke fairly early—I wanted plenty of time in Santa Fe and there proved nothing about the room that compelled me to linger. The water from the showerhead burned with an awful sulfur smell. I came out red and itchy, wishing I hadn’t showered at all. I lay on the bed, hoping for some relief from the wall-mounted air conditioner, air-drying myself on the scratchy comforter. I dressed, finished a bottle of water, and headed out into the sunshine.

I realized mere seconds after pulling out into the street that I’d miscalculated the night before. Much more interesting lodging could be had along the main drag, those motels with their neon signs and general mid-century inclinations. I found coffee and breakfast, explored the enchanting little time capsule of a place, and worked my way back onto the interstate.

There was more: miles of desolate road, lonesome towns, ancient mesas, and towering sandstone peaks as I climbed into the high desert.

I should have expected the dust. I should have known that driving with the windows down invites in more than the clear, high-altitude air; I was careless, not just with the windows, but with the speed at which I traveled down the loose channel of a road, walled in from the high desert and pretending to be invincible. A plume of dust rose behind me. Later, I’d brush the dust off my teeth, scrub it from under my eyes, hear it crunch in the hinges of my eyeglasses. Beach sand feels manageable by comparison; high desert dust permeates completely. In the high desert, I pondered.

There’s a sale on half-pints of whiskey at Costco. Small bottles of liquor always felt romantic to me. Portable. One could slip a half-pint of whiskey into the inside pocket of a jacket and take it with them anywhere.

I have never slipped a half-pint of whiskey into the pocket of anything.

I take all the teabags from every hotel room I stay in. They’re in my backpack. My secret stash. The teabags are there for me, and I’m not really stealing anything.

Just preparing to make tea when everything else falls apart.

On a mountain, I step out of the car and into an Aspen grove, the wind whistling and unexpectedly cold, the view soaring over Santa Fe and a million miles beyond. I realize I’ve been driving all day and have forgotten to eat. I eat a granola bar. I feel panicked. I recline my seat, open all the windows, listen to the wind. I take a Xanax. I fall asleep. I wake up breathing.

To be alone on the road is to experience a kind of freedom, the freedom that severs the ties that bind us to others, even temporarily, but also freedom from our composed and presentable selves. There are two sides to a person: the person they present to the world and the person they present when no presentation is required. Neither person is less real than the other. A person does not require pretense when traveling. One is not at the mercy of normative social structures. One does not worry about their hair, the dust in their clothing, the knots in their shoelaces.

I could imagine the misery of waking up before dawn in a terrible motel room. Early mornings, truly early mornings that in college might have constituted exceptionally late nights, incite a kind of dread in me I can’t quite find comparison for. I feel tired in my bones, I get the kind of headache that feels like gravity pressing down on my brain. My eyes streak red and bloodshot.

It doesn’t matter how early I go to bed, how restfully I sleep—my body rebels against the predawn world.

And so, despite the urging of my wife on the phone, I decided to drive through to Dallas.

I made excellent time across the panhandle and into north-central Texas; the road was all but empty and I felt lead-footed in the dark straight flatness of the highway. I’d made a last stop in Childress for dinner (a Dairy Queen cheeseburger from what I could only describe as the postcard version of a panhandle farming town) and grabbed snacks and bottles of water. I knew I’d have to stop once for gas, but I wanted to drive otherwise unencumbered in the way one can only do alone.

I approached Wichita Falls around midnight, riding the crest of what my father (also an avid late-night roadtrip driver) would call a “second wind.” I stopped for gas. As I neared the monstrous sprawl of Fort Worth, then Dallas, lightning began to illuminate the sky. In a place that flat, you have a perfect panorama of the sprawling horizon, and the lightning was nearly constant. When I hit I-35. it began to rain, huge drops loud against the windshield. It was desolate, nearly 2 a.m. on a Monday night, and the storm raged. It passed exceptionally quickly, and I finished the drive among the sheen of street lights reflecting off wet streets.

I was home, and the city had welcomed me tempestuously. I barely remember stumbling to bed. I rose at dawn to return the rental car and get to work. I’d pushed the boundary between my two lives to a razor-thin line.

No comments