I’m not even a big fan of soup. Now, seven years later, I can’t remember exactly why I ordered it. But I had been struggling with altitude sickness since I arrived in Cusco, Peru, and I must have been looking for something comfortable and familiar like chicken noodle soup to help cure me.

Besides the chicken, the soups had nothing in common. Actually, the soup I received resembled nothing I had ever had in my life. The broth was vermilion—a reddish orange whose subtleties of color foreshadowed its layers of flavors. I expected my first spoonful to be like swallowing a Fourth of July sparkler. And while it was definitely extremely spicy, for the first time in my life, I tasted other flavors mingling with the spice; it was tangy, rich, sharp, salty, and slightly sour. It was exceptional. My weakened system rallied with each sip of the miraculous liquid.

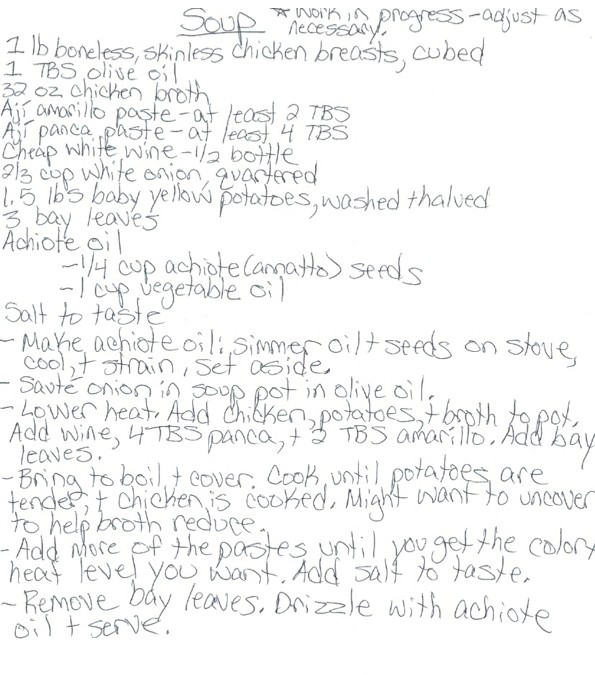

I didn’t want to end my trip and never have this soup again so I asked the restaurant for the recipe. They politely cooperated. The basics were there: chicken, potatoes, and onions. The new-to-me ingredients were there: chicha de jora—a traditional Peruvian fermented corn drink—and pastes of Peruvian peppers including aji amarillo. But strangely absent were any other spices or herbs, or anything that would contribute to the layers of flavor.

Still when I got home, I followed the recipe expecting to soon enjoy a steaming bowl of the soup. But the finished soup didn’t look that appetizing. The pieces of chicken, potatoes, and onion looked dry, jutting out of the measly puddle of broth. It tasted awful, too. I had purchased Peruvian pepper pastes before flying home and had clearly added way too much. I don’t know if the recipe called for this much or if my lifelong hatred of math had caught up with me when converting the metric system measurements. Because I didn’t have any chicha, I substituted beer which left an acrid aftertaste. I couldn’t find the recipe’s huayro potatoes so I used baby yellow potatoes, and maybe this changed the taste as well. Disappointed but not defeated, I began a years-long quest to recreate the soup I loved.

I sought out expert advice; I explained my situation to a Peruvian food writer who suggested additions and substitutions, including the spices I knew had to be present, among them: cumin, oregano, bay leaves, and allspice. Each time I made the soup, I learned which adjustments got me closer to the soup I had in Peru. I learned that cheap white wine was the best substitution for chicha, bay leaves were essential, and adding chicken broth increased the volume of finished soup.

I didn’t immediately include one ingredient the food blogger mentioned: achiote oil. I had never before heard of this ingredient and was a little intimidated. Years later, I spent Christmas with my Venezuelan boyfriend’s family and helped them make hallacas; these are similar to tamales and are made in Venezuela for the Christmas season. I discovered that they drizzled achiote oil in each hallaca before tying it up in plantain leaves. Witnessing this use of the rust-colored oil dissipated any intimidation I initially felt. The next time I wanted to make the soup, I researched how to make this ingredient; I found some annatto seeds, soaked them in vegetable oil, and drizzled the finished oil on top of each bowl before serving.

While my current version of the soup is delicious, it’s not an exact replica of the one I originally had.

When I set out to recreate this soup, I assumed that if I gathered the right ingredients and followed the recipe’s instructions, I could reproduce this dish whenever I wished. But I suspect that even if I had chicha and huayro potatoes, it still wouldn’t be exactly the same because I don’t have two essential ingredients: time and place.

This context of time and place surely affects a dish’s creation and our introduction to it. I know from the food writer I consulted that the soup is usually made with pork, but the chef who made my soup chose chicken instead. How much of that particular chef’s talents, techniques, and choices made up the exact soup I had on that trip?

And how much of my appreciation of the soup is because I associate it with my initial reactions— to my own circumstances at that time and place? I remember being surprised at the soup’s appearance, intrigued by its flavor, and comforted by the relief it afforded me from my dizziness and weakness. I simply can’t recreate that astonishment and transformation.

Not only am I unable to recreate the exact time and place that influenced the original soup and my introduction to it, but I did not anticipate that my own life would inevitably blend with my conception of it.

This soup is all the more important to me because, over the years, it has reflected my changing tastes and increasing culinary knowledge and confidence. Seven years of memories are now mingled with the spicy broth—a veritable archive of the kitchens I once cooked in, the shops where I looked for ingredients, and even the people who mean the most to me.

The truth is I haven’t recreated the soup; I can’t. That soup was as much a product of the place I discovered it as my version is of me. If it can’t be the reproduction I planned, I’d like to think it is an homage—a salute to the original soup that inspired me and to the artistry of Peruvian cuisine.

No comments