Our guide Hassan’s eyes narrowed when he told our group that his people—the Amazigh (pronounced Ah-ma-zeer)—do not like to be called Berbers. Up until then, his tone was light and friendly as he introduced himself, so I was thrown off when I sensed veiled anger. He explained the term Berber comes from the Greek word “barbaros” which we know as “barbarian” in English. Once that sunk in, it wasn’t hard to see why Berber is not a welcomed term, though it is used freely and nonchalantly to identify the Indigenous People of North Africa

Hassan opened my eyes to not only the struggles of his people but the beauty of his language and culture. When we crossed the High Atlas Mountains south of Marrakesh together, I could sense that Hassan felt a deeper connection here. He switched from the jeans he wore in the cities to loose harem pants. The way he spoke to the women in the rug-weaving coop was like they were family. These were his people.

Two of my travel companions had asked Hassan about his life, telling us that we all needed to hear his story. We were now sitting in the bus, watching the snow-capped mountains transition into a dry, rugged, and barren landscape. It took a bit of convincing, but once he started, we knew we were in the presence of a master storyteller. We listened in rapt silence.

As we passed the terracotta buildings of a village, blending into the dusty background before the land opened up again, he told us about being a shepherd, the challenges of going to secondary school, and, finally, passing the exams to get into an elite mountain guide school.

Born in a small village in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Hassan was destined to become a goat herder like many of his peers. He began caring for the flock of a rich family as soon as he was done with primary school at the age of 13. But everything changed the day he spotted a group of foreigners being guided on a mountain trek.

“I liked that image—a man leading people. Similar to a shepherd,” he recalled. “I saw that and I started to dream. Why not me?”

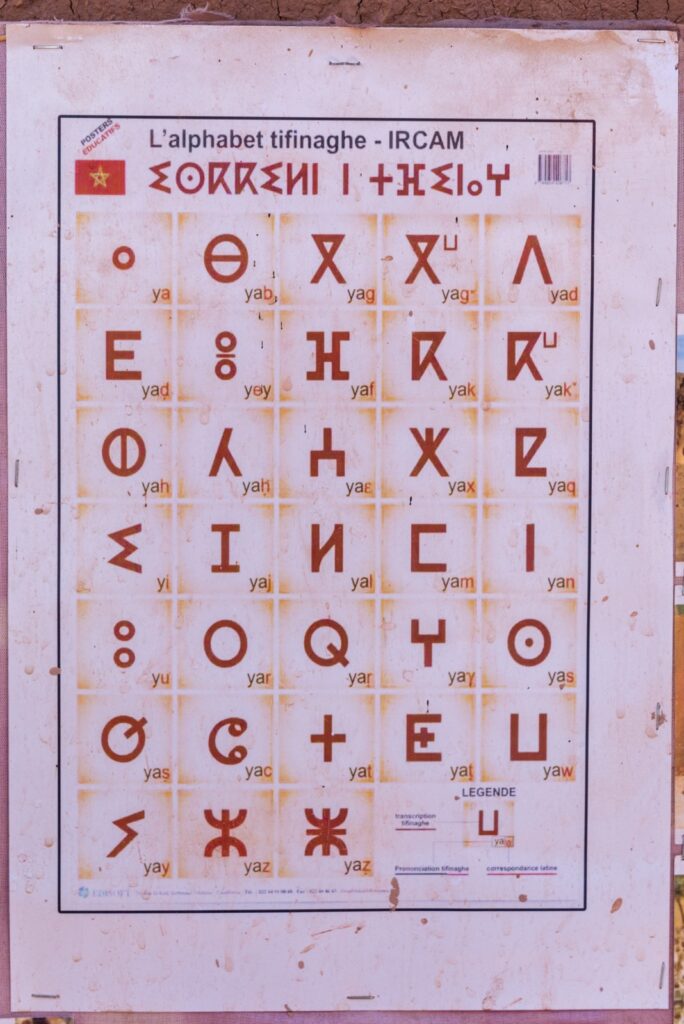

Over lunch on the first day of the tour, Hassan told us that Amazigh, the word they use to identify themselves, means ”free man” and the symbol used in the Tifinagh alphabet that represents this word (as well as the letter z) even looks like a free man: ⵣ.

As old as the Egyptian hieroglyphs, this alphabet is being seen much more since their language, Tamazight, was recognized alongside Arabic as one of Morocco’s official languages in 2011.

In his village, everyone spoke Tamazight. But in the town where the secondary school was, everyone spoke Arabic. Not only did he not know the language well, he also didn’t know a single person in the town. By chance, a family that owned a small restaurant gave him room and board in exchange for his labor. The secondary school was strict and very serious and he struggled to catch up, quickly realizing that his primary school education was very basic because the teachers sent to small village schools are often young, inexperienced, and do not speak Tamazight. Hassan was only thirteen years old—my son’s age.

Recognizing Tamazight as an official language in Morocco was a direct result of the Arab Spring that swept across Northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula that began in Tunisia in December 2010, when a jobless street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire to protest police corruption. This act triggered protests against the ruling government and spread to other states with long-time dictators like Egypt, Libya, Yemen, and Syria. The protests in places where the Amazigh had been oppressed allowed them to join in the demonstrations to demand recognition and respect. While Morocco saw peaceful protests that resulted in changes to the constitution, other countries saw regimes toppled and even civil wars that continue today.

In Algeria, the Tamazight language was recognized after their own “Black Spring” in 2001 and became an official language in 2016. These two countries have the largest populations of Imazighen (the plural form of Amazigh), though they also live in parts of Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and western Egypt—and were the first inhabitants of the Canary Islands.

Wanting to learn more, I spoke with Mr. Lounes Belkacem, one of the founding members and former president of the Amazigh World Congress, who has tirelessly fought for the rights of his people for more than 25 years. “We created this organization that brings together all the Amazigh in 1995. We realized that we were in different countries, under different governments, but had the same issues. We didn’t want to let our cause be confined within the borders of each state. We would export it and use international law to help the Imazighen reclaim their rights. Notably, their rights as Indigenous People.”

There have been waves of colonization that have plagued the Amazigh throughout history. Romans first invaded the north shores of the continent in 146 BC, then Arabs arrived from the East in the 7th century CE and spread west. Finally, Europeans came in the 18th and 19th centuries from France, Britain, Spain, and Italy. Independence came in the 20th century and today, the Arab culture and language remain dominant.

While some progress seems to have been made on paper in some places, reality is another matter. Promises of education being offered in their language, along with the use of Tamazight on official documents like driver’s licenses haven’t always come through. The organization spends much of its time ensuring laws are upheld and defending people who are arrested for reasons including peaceful demonstration or carrying the Amazigh flag.

In Libya, under Muammar Gaddafi, you were not allowed to give your child an Amazigh name. The language and flag were banned and you risked imprisonment or even death for breaking these oppressive laws. While things are still uncertain there, the Amazigh are hopeful that they can finally be free from persecution. In Morocco, you can display the flag and speak the language without risking arrest, but the pressure to assimilate in other parts of Northern Africa is strong.

“There is no animosity regarding all this because this is history. We simply say we no longer want to be colonized. We need to be respected. Our culture is still alive. Our language, customs, traditions, clothing, food. We still live in our homelands. We want to keep our language and our customs. We want to live with Arabs in mutual respect,” says Lounes.

When asked whether he was offended by the term Berber, Lounes says, “We all prefer to call ourselves by our own name, but the term Berber is so widespread that sometimes to facilitate communication, I’ll sometimes say that I am Berber. To be honest, it makes us laugh—to think the Romans attacked us, colonized us—and we are the barbarians.”

“We are conscious that using our name is not what will change things,” he adds. Many are now pushing for an independent state, mostly in Kabylia, where he is from. This territory lies within the borders of Algeria and is about the size of Switzerland, with a population of more than six million. Ninety percent are Amazigh.

“There is a movement for self-determination, but this was declared by the Algerian government as a terrorist movement. It is a political movement, yes, but that defends its ideas peacefully, through the internet and the media. People have been arrested. They are accused of threatening the country’s unity. But their version of national unity is that we are Arab and Muslim. We don’t want more advantages than another, we are just different and we can cooperate.”

Today, Lounes is the Vice Chair of the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. His scope is larger, but he sees the similar struggles of Indigenous People in other parts of Africa and around the globe. Beginning in 2022, the UN declared the Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2032).

On February 28, 2020, over 500 representatives from more than 50 countries met in Mexico City and adopted the Los Pinos Declaration that “emphasizes Indigenous Peoples rights to freedom of expression, to an education in their mother tongue and to participation in public life using their languages, as prerequisites for the survival of indigenous languages many of which are currently on the verge of extinction.”

“Building on the lessons learned during the International Year of Indigenous Languages (2019), the declaration recognizes the importance of Indigenous languages to social cohesion and inclusion, cultural rights, health, and justice—and highlights their relevance to sustainable development and the preservation of biodiversity as they maintain ancient and traditional knowledge that binds humanity with nature.”

The Amazigh have shown great resilience throughout history. In Morocco today, you will see their influence everywhere, in the food, clothing, music, jewelry, and rugs. While many have adopted the Muslim faith, their traditional beliefs have always been connected with the land.

“It’s a way of life. Our way of life is important. We are free, free to choose our beliefs. The place of women in our society, we want women to be free. That they are equal to men, that’s it,” says Lounes.

The cost of freedom today takes a lot of determination and perseverance. Hassan worked hard to finish secondary school and then applied to become a mountain guide. The application process involves a grueling mountain race and only the top finishers get a spot. The day after the race, he could barely walk. But he did manage to go check the results.

“When I saw my name, I saw my dream, right there.”

After nine months of training as a guide, he went to Marrakesh, handing out his resume and waiting for a call on his first mobile phone. The first call took a month. And he almost didn’t go to the interview.

“At the last minute, I decided to go. It took me a long time to find the address. I asked people. I had no idea how to use the elevator so I took the stairs. I met the manager. She was Swedish—first time ever talking to a foreigner. She starts speaking English and I was still learning English. So she said, ‘Do you speak English?’ I said yes, good enough. But I was not good enough by then. I lied because I just wanted to get the job. The interview was maybe one minute. That’s it. She said yes.”

Hassan accepted the job and was to go on his first trip two days later, shadowing a more experienced guide. He had no clothes, no hiking shoes, nothing. When he phoned the guide, he told him everything.

“He became my teacher and he still is one of the most important people in my life. He was an Amazigh from the mountains.”

After the trip, he got his first tip: 500 dirhams (about $56 USD).

“I never, ever got 500 dirhams or even saw 500 dirhams in my whole life. Never. I was so happy. I went directly to a local market when I got back to Marrakesh. I bought new clothes and shoes.”

Three days later, the manager called and offered him his first trip on his own, guiding two young women from Switzerland. Despite being nervous, he admitted that it was his first trip. They simply smiled and said it was their first trip too. All went well and they gave him a good tip.

After that, Hassan moved into a small one-room apartment with five university students who taught him about life in the city and life in general. He worked as a mountain guide and eventually became a tour guide. He helped his brother go to school and finish university. His brother is now a teacher working in the same region where they grew up.

With each twist and turn in Hassan’s story, I kept imagining my own son struggling just to get an education and fighting so hard to reach his goals. Hassan is in his early thirties—younger than me—and has lived a life that couldn’t be more different than my own. His stubborn, resilient dream has already made a beautiful difference in many people’s lives—giving his parents a better life and helping his brother make a positive difference among the next generation. Amazigh people need fewer obstacles and more opportunities to bring their dreams to life. Hassan’s story is deeply inspirational, but his story is the exception, not the rule—yet.

“It was very long and very tough, difficult. It’s life. It’s up and down. All of us are going to face low points but the difference is how are you going to manage? How are you going to overcome those low points? That is the question. Make a mistake? It’s not a problem, just learn and carry on.”

After we reached our Sahara Desert camp and watched the sun set from the dunes, Hassan donned a flowing robe like our Tuareg hosts (a branch of the Amazigh who live in the desert) and joined them around the fire to drum and sing under the stars. I didn’t understand the words but I knew they came from many generations before them, weaving the stories of their people and of the land, while the drums kept the heartbeat of their culture alive.

Marjolein | October 6, 2021

|

Thank you very much for telling the story of Hassan and the Amazigh culture. We are looking forward to hosting travelers so Hassan can show you around beautiful Morocco and tell this and many other stories.

Robert Dixon | October 7, 2021

|

Very much enjoyed this article. I too learned some valuable knowledge.. thank you. It is well written and representing a culture not widely appreciated. Morocco is a county so many tourist come to but many spend their time on the beaches or in the night clubs rather than in the mountain villages and the desert under the stars . So much more to discover and value.

Pingback:About Hassan and Amazigh culture - Travel Magical Morocco | November 12, 2021

|

Charlotte Cassedanne | November 28, 2021

|

What a fantastic piece!

Pingback:Over Hassan en de Amazigh cultuur - Travel Magical Morocco | January 17, 2023

|

Pingback:About Hassan And Amazigh Culture - Magical Morocco | February 22, 2023

|

Pingback:Winner of Gold & Merit at the SATW Bill Muster Photo Awards & Bronze in the Canadian Chapter Awards | Vanessa Dewson | Photographer + Writer | September 25, 2023

|